It is 2005 in Iraq, Baghdad. The United States declared victory in invading Iraq two years prior and overthrowing the dictatorship regime of Saddam Hussain. The provisional government had successfully transferred power to the Iraqi Interim Government, and the Iraqi people had uncommonly elected 275 members to the Iraqi National Assembly. A new constitution was ratified and the tyrant and dictator who had shattered the lives of thousands of Iraqis were captured and put on trial to be prosecuted for all his crimes.

It sounds like the perfect shape of a healed country, which not only had just gotten out of a war with the United States but also years and years of dictatorship and totalitarianism. But in reality, that was not the case. As perfectly restored as Iraq sounded in the books in the years 2003 to 2006, the state of the country was nonetheless chaotic, to say the least. The insurgency period in Iraq at that time was still prominent in opposition to the US invasion and was paving the way to the most violent phase of the Iraq War, the 2006 sectarian civil war. As an Iraqi living in Iraq during and after the 2003 war, I remember the rampant looting after the invasion and the chaos that infested the country when there was no rule of law or stable political powers in place. I also remember dozens of suicides and bombing attacks, the hundreds of bodies scattered in the streets, and the persistent uncertainty and fear roaming inside every household in the country. These memories were reflected in statistics that showed in the years 2005 and 2006, the death toll of Iraqis was surging daily. In 2005, 6.1 out of every ten thousand Iraqis were killed, a number equivalent to “eliminating Tallahassee.” In 2006, the numbers went even higher with the rise of the deadliest phase in Iraq with 10.7 out of every ten thousand Iraqis were killed, an amount “[e]quivelent to 318,000 American deaths – the population of St. Louis.” According to the Failed States Index, Iraq was in the top five unstable countries in the world in the years 2005 and 2006.

While all of that was taking place, the dictator who implanted fear in every Iraqi for years was being prosecuted in the heart of all this chaos, in the country’s capital, Baghdad. Saddam Hussein’s trial started in October 2005 and continued until he was found guilty and sentenced to death in December 2006. Many questioned the legitimacy and legality of the tribunal that tried him, the Iraqi Special Tribunal, which was later renamed the Iraqi High Tribunal (Tribunal). Many criticized the influence that led to the establishment of the Tribunal, including Saddam himself during the trial. But one important angle of this trial remained highly problematic yet less examined: the timing of the trial in those deadly years in Iraq. In specific, the extent to which the security instability in 2005 and 2006 had compromised the fairness of Saddam Hussain’s trial and the success of the Tribunal as a whole.

The Iraqi Special Tribunal Coming Into Existence

On December 10, 2003, the members of the Interim Governing Council of Iraq announced the establishment of the Iraqi High Tribunal, which was charged with prosecuting Saddam Hussain and other members of the Baath party of his regime. This establishment came after a wide examination at the international level, which was specifically reflected in the report of the Transnational Justice Project under the International Human Rights Law Institute. The report found that “the overwhelming majority of Iraqi jurists supported a national law to establish a special national criminal court comprising of Iraqi judges per law no. 23/1971,” which may “seek council from international experts or have international judges acting as experts.” Similar support was found among the Iraqi population, which was reflected in a study conducted by the International Center for Transnational Justice and the Human Rights Center at the University of California at Berkley in the summer of 2003. The study showed that Iraqis expressed a “clear and emphatic preference for any court to be established in Iraq and to operate under Iraqi control.”

In Washington, however, at first, politicians “favored a hybrid tribunal that would be based on the dual authority of the United Nations and the government of Iraq and would fully integrate international lawyers alongside Iraqis in the trial chambers, prosecutorial offices, and appeals panels.” This preference did not last, however, because ultimately everyone wanted to empower Iraq to have its full control over the Tribunal while relying solely on Iraq’s legal system. The overarching aim was to “help re-establish Iraqis’ trust in the judicial system and its protection against the deprivation of rights, which has been strongly eroded by the past 23 years of Saddam’s reign.”

Therefore, a discussion for a new domestic court emerged to meet the expectations and preferences of the Iraqis. In mid-April of 2003, a resolution was passed by the United Nations, where the Security Council required the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) to “comply fully with their obligations under international law including, in particular, the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the Hague Regulations of 1907.” In response, per the inherent powers granted to it as an occupant and per the empowerment received specifically from the Security Council, the CPA stated that it is “vested with all executive, legislative, and judicial authority necessary to achieve its objectives.” Accordingly, the CPA granted temporary legislative authority to the Iraq Governing Council in 2003 to pass a law that established the Tribunal. A statute was passed as a result of establishing the Iraqi Special Tribunal, and Paul Bremer, the Chief US Administrator in Iraq at the time, signed it into law on behalf of the CPA. The United States then funded a total of $128 million to install the Tribunal and support its functioning in Baghdad.

However, even though everyone wanted the Tribunal to be under the full control of Iraq and its laws, the Tribunal’s jurisdiction and structure did not follow the ordinary judiciary system of Iraq. The Tribunal had jurisdiction over Iraqis and non-Iraqis who were residents of Iraq for crimes committed from July 17, 1968, up until May 1, 2003, in the territory of Iraq or elsewhere. In terms of crimes to be prosecuted, the Tribunal integrated Iraq law into the existing international criminal law and humanitarian law, which both were unknown to Iraqi judges at the time.

The Tribunal was only allowed to investigate and try crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and other violation of certain Iraqi laws, including attempting to manipulate the judiciary, the wastage of national resources and public assets, and “the abuse of position and the pursuit of policies that may lead to the threat of war.” The Statute of the Tribunal further specified the qualifications of the judges to preside over cases, which were all required to be Iraqis, but who must also “appoint non-Iraqi nationals to act in advisory capacities […] and provide assistance to the judges with respect to international law.”

The Trial: Chaos Inside And Outside The Courtroom

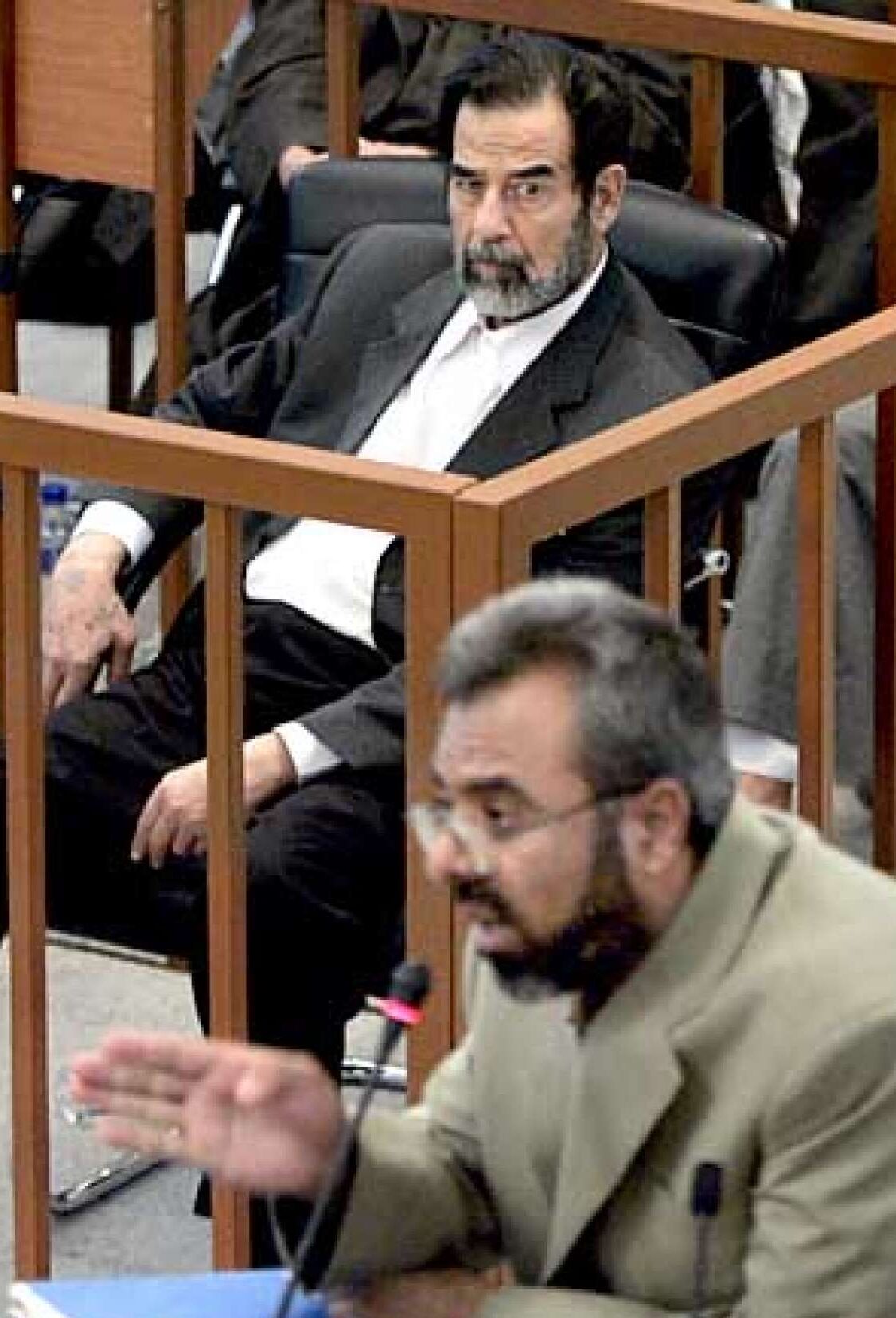

After the Tribunal came into existence and became fully functioning in 2005, Saddam was brought under investigation after his capture for the hundred ordered executions and torture of Shia civilians in Dujail in 1982. After the investigation, the inspective judges found overwhelming evidence to send Saddam to trial at the Tribunal alongside his accomplices from the Baath party, all to be prosecuted for crimes against humanity in the Dujail massacre.

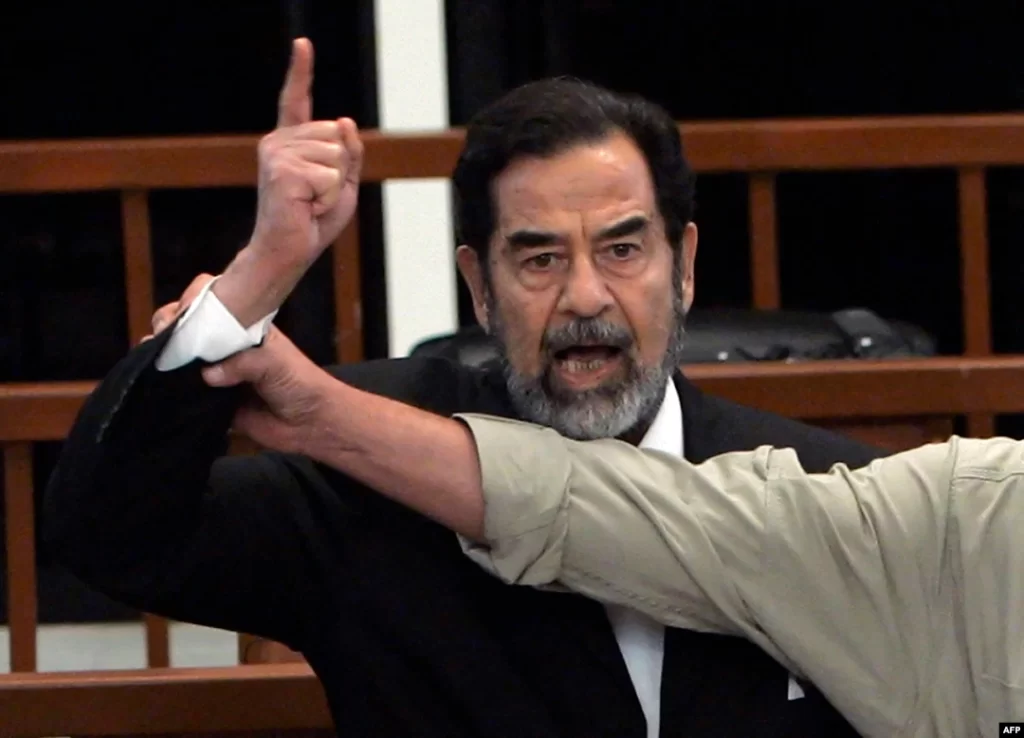

Once the trial began, chaos, fear, and uncertainty roamed inside and outside the courtroom. From the outset, Saddam did so much during the trial to derail the process and turn it into a circus. Saddam’s strategy, which ultimately became the strategy of all defendants in this case, was to discredit the Tribunal and show to the world that the Tribunal was not a credible court to try and prosecute him for international crimes. To him, making the world believe that the Tribunal was an illegitimate court would also make people perceive the process as unjust, or rather as an “appearance of victor justice” reflecting what the United States allegedly wanted it to be. Saddam also had the objective of making the trial drag for months, if not years, because it would prolong the possibility of the death penalty being imposed at the end. More importantly, Saddam wanted to tarnish the image of the judges and the prosecution at the international level, and to implant fear in anyone who would be part of the trial in any manner that would contribute to his conviction. This not only raised fear among judges, lawyers, and witnesses, but it also made things unpredictable outside the courtroom since many of Saddam’s followers were ready to act against anyone who threatened the freedom of their leader. After all, Iraq was on the edge of a sectarian civil war. The trial itself gave the Iraqis at the time another issue to divide them on sectarian lines, with Shias calling for his execution and Sunnis praising his presidency and condemning the trial’s legitimacy.

Saddam’s strategy contributed more to the instability and insecurity outside and inside the courtroom because Iraq law allowed it. Under Iraq law, Defendant has control over the trial, unlike the proceeding in western legal systems. In specific, Defendant has the right to participate in the defense and to question witnesses in his own trial. The Statute of the Tribunal reverted to this Iraqi legal standard and allowed Defendants in its proceedings to have control in the courtroom. This meant that Saddam was allowed to question witnesses who were testifying against him.

Putting this into perspective, you see a person who was feared by every single Iraqi in the country question witnesses on the stand who were accusing him of crimes. People who would face instant death if they stood against Saddam when he was in power were coming to court and being questioned by him directly. Knowing the fear that he implanted in Iraqis and the possible threats of death that might result from their testimonies against Saddam, witnesses were given the option to cover their faces to testify anonymously. Similarly throughout the trial, except for the Presiding Judge, “the faces of the other four judges would never be revealed for security reasons.” Additionally, the courtroom itself “was barricaded behind rows of vehicle barriers and guardhouse, and security was at least three levels thick.”

However, despite all these security precautions, many judges, lawyers, and witnesses nonetheless faced death for their participation in the trial. Three of the lawyers were assassinated mid-trial. Only one day into the trial, one of the defense lawyers was kidnapped by a group of armed men and shot dead the same day. A few days later, two of the other defense lawyers were attacked and killed. The killings continued with at least eight dead, including one judge. Additionally, even if not faced with death, judges quit the trial because of outside influence. The first Chief Judge ruling on the case, Rizgar Muammed Amin, resigned in the early proceedings amid high criticism of his handling of the case. A second judge, who was in line to replace Amin, was barred from presiding due to ties to Saddam Hussein and the Baath party.

Unsurprisingly, Saddam took advantage of all this disorder. There was a moment during the trial where Saddam “wagged his finger and threatened death to any lawyer who spoke against him,” accusing anyone who would testify against him to be the “enemy of the state.”

This statement on a nationwide, and even worldwide, televised trial coming from a tyrant, like Saddam, was essentially a death threat and a message to his followers outside the courtroom to find those who speak against him and to kill them and their families. Similarly, in many clips of the trial, Saddam appeared to be having his moment multiple times while judges silently allowed it per Iraq’s law. Taking advantage of that, so many times Saddam specifically spoke to the insurgencies and conflicts taking place outside of the courtroom that had nothing to do with the trial nor the legal merits of the case.

All these security challenges delayed the proceedings multiple times. From transporting witnesses, lawyers, and judges (from and to the Tribunal), to controlling disorder inside and outside the courtroom, the trial kept on dragging for days and months. More importantly, the security concerns outside the courtroom in Iraq were ignited because of the chaos of the trial, and vice versa. Many times during the trial, Saddam “tried to communicate the secret location of the courthouse to his supporters watching the broadcast.” As a result, insurgents tried on many occasions to attack the courthouse but were arrested before succeeding.

In sum, there is an agreement among many legal scholars worldwide that Saddam’s trial “will no doubt be remembered as one of the messiest trials in legal history.”

Legal Implications: Violations of International Standards of Fairness and Due Process

Thus, with all this messiness and instability inside and outside the courtroom, what legal concerns do the trial and the Tribunal raise?

To begin, structurally, there are multiple legal concerns regarding the legitimacy of the Tribunal and its effectiveness in delivering a fair trial. The primary concern was Iraq’s status at the time as occupied territory by the United States and the law-making power of the CPA. Although the purpose of this blog is not to extensively examine whether Iraq was legally occupied or not at the time, Articles 42 of the Regulations annexed to Hague Convention IV of 1907 led to the premised conclusion that a belligerent occupation did exist. Article 42 states that a “territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army.” Article 42 is met by two main instruments, the Coalition Provisional Authority Regulation No. 1 and Security Council Resolution 1483, which both authorize the temporary exercise of power by the CPA in Iraq.

Thus, the concern regarding CPA’s lawmaking authority during a belligerent occupation is mainly in reference to Article 43 of the Hague Regulations and Articles 64-67 of the Geneva Convention IV of 1949. Both legal instruments impose limitations on rescinding past laws and passing new ones in an occupied state. In specific, Article 43 of the Hague Regulation states that “the authority of the legitimate power having actually passed into the hands of the occupant, the latter shall take all the steps in his power to re-establish and insure … public order and safety, while respecting … the laws in force in the country.” Similarly, Article 64 of the Geneva Convention states that “[t]he penal laws of the occupied territory shall remain in force … [and] the tribunals of the occupied territory shall continue to function in respect of all offenses covered by the said laws.” Additionally, Article 66 of the Geneva Convention requires that “the Occupying Power may hand over the accused to its properly constituted, non-political military courts, on condition that the said courts sit in the occupied country.” However, similar tribunals have shown a different practice contrary to the language of Article 66 due to security reasons, specifically the ICTY and ICTR, in which both were located outside the locus delicti commissi.

Applying these international law requirements to the Tribunal, the CPA granted temporary legislative authority to the Iraq Governing Council in 2003 to pass a law that established the Tribunal. A statute was passed as a result of establishing the Tribunal, which then later was passed into law on behalf of the CPA. Following that, the Iraqi Governing Council adopted the Transitional Administrative Law to function as an interim constitution for Iraq until a permanent one could be adopted. However, the interim constitution, specifically Article 15(I), clearly established that “a special or exceptional court may not be established.” Accordingly, in reliance on these legal instruments, international scholars, and Saddam Hussein himself, argued that the Tribunal was unlawful because the occupying power did in fact create new laws and legal institutions that were meant to exist beyond the time of the conflict, an alleged violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Similarly, it can be argued that it is a violation of international law and standards to allow the occupying powers to prosecute crimes that occurred prior to the occupation.

Additionally, even though the Tribunal structurally had the capability of delivering a fair trial, procedurally, it was not a fair one despite the final verdict. The Tribunal was created with the goal of following international standards of due process. Meaning that, even though the Tribunal was a domestic court, it was operated under a special charter that was empowered by international law with special rules that incorporates international criminal procedure into its operation. But, the messiness and chaos throughout the trial reflect that such standards were not followed. Iraq is a party to the International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), thus subject to the requirements of Article 14 that set many conditions for a fair trial proceeding. Even though many of those guarantees were outlined in the Statute, the Tribunal still reflected many shortcomings. Specifically, it left out the guarantees that concern those who participated in the proceedings in any capacity.

Judges, lawyers, and witnesses were terrorized for their involvement in the trial and were not protected from such threats and terrors nor were given legal immunity from future criminal prosecution — which was highly possible given the instability of the political situation and governing bodies of Iraq at the time. This is contrary to Article 48 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the Agreement on Privileges and Immunities of the ICC, which provides extensive legal protections for officials and staff, including counsels, judges, witnesses, and others. Additionally, the Tribunal’s Statute also failed to guarantee any rights or protections for witnesses and victims of having a counsel present during their testimonies. The presence of legal counsel to victims and witnesses is essential to ensure they receive legal support during their participation, which is an international standard set and followed by the ICC and guaranteed by Principle 6(b) of the UN Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power. Moreover, Rule 18(b) of the ICC requires the separation of services between prosecution and defense witnesses, which was not specified nor followed by the Tribunal.

Additionally, Rule 18(b) is specifically set to ensure the impartiality and fairness of all parties involved. The criteria established by the Statute for appointing judges were strictly set to Iraqis only and lacked any specification of international law standards of competency and impartiality. Judges’ impartiality was also jeopardized by the high likeliness that they themselves had been affected by Saddam’s reign. Similarly, a limited criterion on nationality was also set for defense counsels, thus excluding the expertise of many qualified lawyers who may be more competent in international law crimes. Even the standard of proof did not follow the standard set by international law. The standard of proof followed by the Tribunal, as outlined by Iraq law, was not that of “beyond a reasonable doubt,” but rather “based on the extent to which it is satisfied by the evidence presented.”

In addition to all these legal deficiencies in the language of the Statute, the overarching aspect of international law that the Tribunal lacked was compliance with Article 14 of the ICCPR, which requires a “fair and public hearing by a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal established by law.” This requirement raised major concerns given the unstable and insecure state of Iraq at the time. A fair proceeding is even harder to guarantee in an unstable country because counsels will encounter many challenges “in locating and protecting witnesses, obtaining access to documents, and securing the attendance of international experts it may wish to call in support.” Thus, due to high-security concerns, the Tribunal had to rely heavily on the Coalition Forces and foreign personnel, reflecting a further lack of independence and impartiality.

Thus, structurally, and procedurally, the Tribunal and the trial had many legal shortcomings that violated international law and standards. The killings of witnesses, judges, and lawyers, the resignation of judges due to outside influence, the death threats inside and outside the courtroom, and the foreign interference and influence in the proceeding, were all contradictions of what international law requires as to a court’s independence, impartiality, and fairness. All of those challenges could have been easily prevented if Saddam was tried at a competent international tribunal that had far more expertise in handling similar cases and stronger capabilities of ensuring fair proceedings and protecting trial participants. The initial aim of establishing a domestic tribunal was to restore Iraqis’ faith in a legitimate and strong rule of law. But the verdict alone of executing Saddam was not enough to reflect the proper model and expectations of a legitimate judiciary system that should be followed in every country.

To this day, Iraq lacks a proper rule of law. It is even doubtful to say that Iraqis learned anything from the trial of Saddam, besides the reinforcement of the image that law in Iraq is nothing but a mix of chaos and uncertainty. Even years after Saddam’s trial, the Tribunal was never used as a forum and a model to hold accountable heads of state who commit inhumane crimes against Iraqis. In fact, following the deadly October Revolution of 2019, Iraqis are still waiting for a court of law to hold Adel Abdul Mahdi accountable for the deaths of more than 600 Iraqis who were brutally killed for peacefully demonstrating against the government. Abdul Mahdi is just another example of a former ruler of Iraq who would, in technicality, fall under the Tribunal’s jurisdiction but was nonetheless neither investigated nor tried for his inhumane crimes of ordering the killings of peaceful protestors.

Thus, did the Tribunal and the trial of Saddam Hussain really restore Iraqis’ faith in their legal system? I argue not. Conversely, if the trial was held at the international level by a well-established tribunal and competent lawyers and judges, then Iraqis would have certainly learned that, even if their domestic legal system fails them, the international judiciary system has their back. If the trial was not held in the most chaotic and unstable years of Iraq, a more exemplary trial would have resulted, thus setting a precedent for Iraq on how to properly prosecute future tyrants. It would have also negated the fallacy that justice can be effectively reached by relying on chaos and disorder.

Up until Saddam’s trial, almost everyone who ruled Iraq in any capacity was removed from power using violent coups — a statement that is true for many rulers in the Middle East region. Saddam Hussein’s trial was an unprecedented attempt to hold a tyrant accountable fully domestically through the rule of law. However, although the attempt resulted in a verdict that exhibited a sense of justice to all those affected by Saddam’s barbaric actions, it nonetheless presented a chaotic proceeding that cannot possibly be used as a model to hold future rulers accountable for inhumane crimes they commit against their people. Thus, it is doubtful that the people of Iraq, or any other unsteady country in the Middle East, would rely on the Iraqi Special Tribunal and the trial of Saddam Hussein as an efficacious example to resort to the rule of law, instead of violence, when removing a tyrant from power.

As shown by the troubling statistics inside and outside the courtroom in Iraq in the years 2005 and 2006, it is safe to conclude that security instability made the trial proceedings a circus. The trial was flawed, and the proceedings broadcasted a political theater that violated many international laws and standards. The final verdict did offer a taste of justice to Iraqis, but the proceedings will forever reflect a chaotic and incoherent attempt of integrating international law into a domestic legal system, without serious consideration of the country’s stability and security. After all, a court that could not protect its judges, witnesses, and lawyers from death while its proceedings were ongoing cannot possibly be seen as an effective forum capable of delivering fair trials and justice. The only impact the trial had, and continues to have, even 19 years after the invasion, is that Iraq will forever be remembered for having held the “messiest trial in legal history.”

Thanks for your blog, nice to read. Do not stop.