At the High Line, a popular tourist attraction in New York City, visitors to the West Side of Lower Manhattan ascend above street level to what was once an elevated freight train line and is now a tranquil and architecturally intriguing promenade. Here walkers enjoy a park-like openness; with fellow strollers they experience

urban beauty, art, and the wonder of comradeship.

In late May, a Predator drone replica, appearing suddenly above the High Line promenade at 30th Street, might seem to scrutinize people below. The “gaze” of the sleek, white sculpture by Sam Durant, called “Untitled, (drone),” in the shape of the U.S. military’s Predator killer drone, will sweep unpredictably over the people below, rotating atop its 25-foot-high steel pole, its direction guided by the wind.

Unlike the real Predator, it won’t carry two Hellfire missiles and a surveillance camera. The drone’s death-delivering features are omitted from Durant’s sculpture. Nevertheless, he hopes it will generate discussion.

“Untitled (drone)” is meant to animate questions “about the use of drones, surveillance, and targeted killings in places far and near,” said Durant in a recent statement, and to ask “whether as a society we agree with and want to continue these practices.”

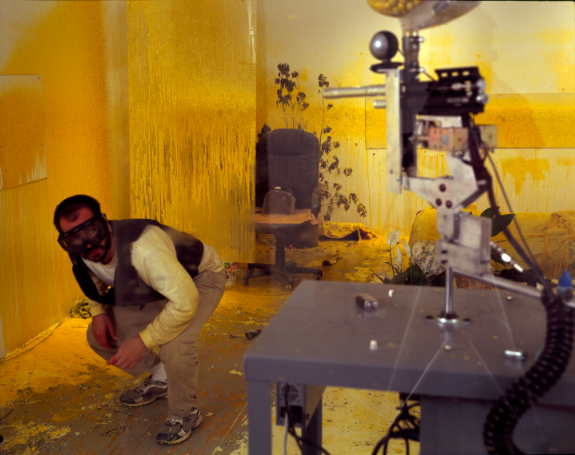

In 2007, a similar concern about remote killing motivated New York artist Wafaa Bilal, now a professor at NYU’s Tisch Gallery, to lock himself for a month in a cubicle where, any hour of the day or night, he could be remotely targeted by a paint-ball gun blast. Anyone on the internet who chose to could shoot at him.

He was shot at more than 60,000 times by people from 128 countries. Bilal called the project “Domestic Tension.” In a resulting book, Shoot an Iraqi: Art, Life and Resistance Under the Gun, Bilal and co-author Kary Lydersen chronicled the remarkable outcome of the “Domestic Tension” project.

Along with descriptions of constant paint-ball attacks against Bilal, they wrote of the internet participants who instead wrestled with the controls to keep Bilal from being shot. And they described the death of Bilal’s brother, Hajj, who was killed by a U.S. air-to- ground missile in 2004.

Grappling with the terrible vulnerability to sudden death felt by people across Iraq, Bilal, who grew up in Iraq himself, chose to make himself vulnerable to those who might wish him harm – to partly experience the pervasive fear of being suddenly, and without warning, attacked.

Three years later, in June of 2010, Bilal designed the “And Counting” art work in which a tattoo artist inked the names of Iraq’s major cities on Bilal’s back. Overlaying the cities were placed “dots of ink, thousands and thousands of them — each representing a casualty of the Iraq war. The dots are tattooed near the city where the person died: red ink for the American soldiers, ultraviolet ink for the Iraqi civilians, invisible unless seen under black light.”

Bilal, Durant and other artists who help us think about U.S. colonial warfare against the people of Iraq and other nations should surely be thanked. Art and stories help us make sense of the realities we face.

The pristine, unsullied drone may be an apt metaphor for twenty-first-century U.S. warfare, which can be entirely remote. Before driving home to dinner with their loved ones, soldiers on another side of the world can kill suspected militants miles from any battlefield. The people assassinated by drone attacks may themselves be driving along a road, possibly headed toward their own family homes.

U.S. technicians analyze miles of surveillance footage from drone cameras, but such surveillance doesn’t disclose information about the people a drone operator targets.

In fact, as Andrew Cockburn wrote in the Dec. 2020 London Review of Books: “the laws of physics impose inherent restrictions of picture quality from distant drones that no amount of money can overcome. Unless pictured from low altitude and in clear weather, individuals appear as dots, cars as blurry blobs.”

Bilal’s exploration, on the other hand, is deeply personal, holding in mind the anguish of individual victims. Bilal took great pains, not least the pain of getting tattooed, to name the people whose dots appear on his back, people who had been killed.

Contemplating “Untitled (drone),” it’s unsettling to recall that no one in the U.S. can name even one of the thirty Afghan laborers killed by a U.S. drone in 2019. A U.S. drone operator fired a missile into an encampment of migrant workers resting after a day of harvesting pine nuts in Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province. An additional 40 people were injured. To U.S. drone pilots, such victims may appear only as dots.

In many war zones, human rights documentarians risk their lives every day to record the testimonies of people suffering war-related human rights violations, including drone attacks striking civilians. Mwatana for Human Rights, an organization based in Yemen, researches human rights abuses committed by all sides in the war raging there. In their report, Death Falling from the Sky, Civilian Harm from the United States’ Use of Lethal Force in Yemen, they examine 12 U.S. aerial attacks in Yemen, 10 of them were U.S. drone strikes, between 2017 and 2019.

They report at least 38 Yemeni civilians—nineteen men, thirteen children, and six women—were killed and seven others were injured in the attacks.

They tell us of important roles the slain victims played as family and community members. We read of families bereft of income after the killing of wage earners, including beekeepers, fishers, laborers and drivers. Students described one of the men killed as a beloved teacher. Also among the dead were university students and housewives. Loved ones who mourn the deaths of those killed still fear hearing the hum of a drone.

It’s now clear that the Houthis in Yemen have been able to use 3-D models to create drones which they have fired across their own border, hitting targets in Saudi Arabia. This kind of proliferation has been entirely predictable.

The U.S. recently announced plans to sell the United Arab Emirates fifty F-35 fighter jets, eighteen Reaper drones, and various missiles, bombs, and munitions. The UAE has used its weapons against its own people and has run clandestine prisons in Yemen where people are tortured and broken as human beings, a fate awaiting any Yemeni critic of their power.

The installation of a drone overlooking people in Manhattan can bring them, too, into the larger discussion.

Right outside of many military bases safely within the U.S. – the very bases from which drones are piloted to deal death over Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia, Syria, and other lands, activists have repeatedly staged artistic events. In 2011, at Hancock Field in Syracuse, thirty-eight activists were arrested for a “die-in” during which they simply lay down, at the gate, covering themselves with bloodied sheets.

The title of Sam Durant’s sculpture – “Untitled (drone)” – means that in a sense it is officially nameless, like so many of the victims of the U.S. Predator drones it is designed to resemble. People in many parts of the world can’t speak up. Comparatively, we don’t face torture or death for protesting. We can tell the stories of the people being killed right now by our drones, or watching the skies in terror of them.

We should tell those stories, those realities, to our elected representatives, to faith-based communities, to academics, to media, and to our family and friends. And if you know anyone in New York City, please tell them to be on the lookout for a Predator drone in lower Manhattan. This pretends drone could help us grapple with reality and accelerate an international push to ban killer drones.

Disclaimer: A version of this article first appeared at The Progressive.org

Kathy Kelly is a Chicago-based peace activist and author working to end U.S. military and economic wars. At times, her activism has led her to war zones and prisons. Her writing has been published in CounterPunch, the Catholic Worker, and The Progressive Magazine. She is a three-time Nobel Peace Prize Nominee and a published author of a book, Other Lands Have Dreams. Kathy.vcnv@gmail.com